Ramon Hernandez works to stay positive

Oakland Tribune

Article Last Updated: Wednesday, May 07, 2003 - 6:24:12 AM PST

OAKLAND -- Ramon Hernandez would be perfect for one of those before and after ads. This isn't about his weight. He's still the same solid 210 pounds, thus hardly in need of a crash diet.

The before and after angle has to do with baseball. A .247 lifetime hitter after a career-low .233 in 2002, Hernandez began Tuesday at .349, tops among Oakland A's hitters and sixth in the American League.

Ramon Hernandez? The catcher once perceived as the A's weakest link? His leap offensively follows his advancement defensively. He threw out 21.8 percent of base stealers in 2000, his first full season in Oakland. He gunned down 31.8 percent last year, sixth best percentage in the AL.

Critics were harder on Hernandez than were his A's teammates, who give him a strong performance rating.

OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS SECTION

5/13/2003

- A's develop winning plan

- Expos' victory spoils a good day for Alou

- NBA hits, misses for ESPN, ABC

- Kidd hot as Nets sweep Celtics

- Livan happy to be back in S.F.

- Gates to Hall of Fame remain sticky

- Funny Cide jockey cleared of wrongdoing in Derby victory

- Basketball scholarships reunite Parker brothers

- Annika's entry tees off Singh

- Montreal's 'El Duque' has shoulder surgery

- Lopez and Sheffield fuel Braves' outburst at L.A.

- Woods skips Colonial, cuts schedule before Open

- Jackson back, will coach Lakers

- Another shutout by Giguere gives Mighty Ducks 2-0 lead

- Cal women capture regional by 20 shots

- De La Salle wins boys team title

"He's a great defensive catcher," Tim Hudson said. "What I like best about him is the game he calls. He understands our pitching staff, what works for a pitcher on a particular day. There's definitely a comfort zone. And he's done a great job of studying hitters."

Before Tuesday's series opener with Chicago, Hernandez discussed his overall improvement, what it's like to catch Oakland's Holy Trinity, Ted Lilly's addition to the rotation, and the physical demands of catching with Dave Newhouse of ANG Newspapers.

Q. How did you raise your batting average so high?

A. Work hard every day, think all the time positive. Keep off a lot of pressure, and go out and try to enjoy the game.

Q. Have you made any technical changes?

A. A little bit. I've short-

ened my swing a little bit. Working with the hitting coach (Thad Bosley), it's gotten shorter. Now I'm trying to get good pitches to hit.

Q. What is your goal in terms of a season average?

A. If you asked everybody, they might say .280, .290, .300. I don't know where I'm going to finish, but I want to finish the season strong.

Q. Don't overanalyze it, right?

A. Yeah. Don't try to think too much. Don't over-do things. Go out and give it your best shot. That's all.

Q. How, specifically, did you get better at nailing basestealers?

A. Every year you get older, and you're going to learn more things to help you throw guys out. To do that, you have to be consistent throwing to second base. Just be you.

Q. Would you say, though, it's improved footwork rather than increased arm strength that has improved your percentage?

A. Yeah.

Q. Don't be modest. How much are you responsible for the success of A's pitchers, who lead the AL with a 3.25 ERA?

A. I just suggest to them. But they've got the ball, and they're the ones who make the final answer. They prepare themselves pretty good, and every one of them knows what they want to do out there. So that makes my job a little easier.

Q. What kind of suggestions do you make?

A. I just say, "Hey, same game. Slow down a little bit. Give it your best shot. If it works, good. If it don't work, don't put your head down." Try to do your best. Don't take it too personally. Everybody is human.

Q. How do Hudson, Mark Mulder and Barry Zito differ on the mound?

A. Mulder throws more away to righties. Zito throws more in to righties. Hudson throws more in to righties and a little bit away to lefties. They're totally different pitchers.

Q. What must you do to get their best?

A. Just keep them in the game. Keep them calm. That's all.

Q. What's the most amazing thing about them?

A. They're winners. They only think positive. And they don't feel any pressure when it's clutch time and they have to make a pitch.

Q. Can Lilly make it a Big Four?

A. I hope so. He has a strong mind. Every time he's out there, he thinks he's the best. That's a big key to being a starting pitcher.

Q. Have you caught minor league sensation Rich Harden?

A. One time in spring training. Something like three innings. He has great stuff. Throws very hard. All he needs is a little more experience.

Q. Can closer Keith Foulke have the same success that Billy Koch had last year in Oakland?

A. Yes. When he comes in in the ninth inning, he knows what he's going to do, and he's totally comfortable.

Q. With free agency, how difficult is it for you to catch new pitchers every year?

A. It's OK if you've been with one club a long time. But if you go to a new club, you have to learn how guys pitch, what they like to throw on different pitches, what pitches they like to use to strike out guys.

Q. What's the hardest part of catching physically?

A. It's the whole body. It's more mentally. You wake up in the morning and say you've got no chance to play. You've got to be strong mentally and tell yourself that you can go. You've got some pain. Try and take care of your body so you can play every day.

Q. What is your condition at the end of a season?

A. My knees are sore. My arm is tired. My shoulder is very tired.

Q. Broken fingers?

A. No, nothing like that so far, thank you.

Q. You're 27. Could you catch 10 more years like Benito Santiago?

A. I want to. I hope so. I'm going to try and work for that. He's one of the guys I look at as a big example.

Q. If all the big league catchers got together and picked a favorite catcher who's in the game today, who would he be?

A. Today, I say ... it's hard. I would pick Benito Santiago for how old he is (38) and how many years he has played in the big leagues (18). He has a strong mind, he has been through a lot of things, and he's catching every day.

Q. With the progress you've made, are you a future All-Star?

A. I want to be, but it's hard to tell. There's a lot of good players out there, a lot of good catchers. I want to prove myself at that position, but I can't forget I have to work hard every year, work hard all the time.

Q. How popular are you back home in Venezuela?

A. I don't like to make myself too popular. People think they know me. When they try to get my attention, I give it to them. I go to schools. I do clinics back home. I like to do things for little kids.

Q. Did criticism of your catching ever get to you?

A. My first year was the toughest ever. When we got to the end of the year, and we had to win a game, the catcher's a big part of it. I had a lot of pressure on me. When I got through that ... the last two years have been hard, but not as hard as that 2000.

Q. Do you have a lot of self-confidence?

A. Yeah. I always think positive. Even if the worst can happen, all I can do is keep my head up, and forget the days in the past.

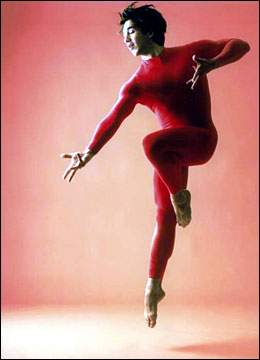

DANCE--On the Move: Breath, water, and the "sensuality of movement"

<a href=www.richmond.com>Richmond.com

Wednesday May 7, 2003

It's a fallacy that "we need to be experts in order to enjoy something," says Juan Carlos Rincones, director of Rincones & Company Dance Theater. He deplores this all-too-common view, and says that the most rewarding thing for him is to connect with an audience, whether or not they are dance connoisseurs. "I feel that every audience member brings their own background, human story, and emotions of the moment" to bear on the interpretation of a performance, Rincones says, and he enjoys hearing comments from people who have seen elements in his work that he may never have intended.

Richmond audiences can draw their own conclusions from Rincones' work Thursday night at the Grace Street Theater, when the director and his company perform here for the first time. The program consists of new work, which Rincones refuses to discuss because he prefers "to have the audience see new pieces without any preconceived ideas," and in the second half, a repertory piece called "Torrentes."

Set to Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Op. 38, "Torrentes" reflects Rincones' "intense commitment to become intimately acquainted with the music." Music is a big component in his choreography, and while that may seem an obvious statement about a dancer, many choreographers work out movement first and find music later, or set work to no music at all. Not Rincones. "Music is my motivator," he says.

"I was very afraid of [the Barber music] at first because I couldn't count it." By approaching the music on his own terms, however, and understanding it as a dancer rather than as a musician, Rincones found he could make his own score through movement, and got past his fear of the concerto's intricacies.

Communicating this approach to his dancers, Rincones encourages them to feel the music through their breathing. Classical ballet, for example, downplays the movement of breath in the body, but Rincones likes to make that movement of breath part of the larger movement of the dance, and so "convey the music in a three-dimensional way." About "Torrentes" he says, "For me, the music evokes the forces of nature; in particular the rushing flow of water I associate with my native Venezuela."

Choreography for Rincones is a "quite uncomfortable" process that involves finding a quiet internal space to work out the progression from music to breath to movement. Once he's moving, he works in "wide brush strokes," sketching out loose movement phrases that he then begins to manipulate and define. Dance, he says, means "trying to communicate with the body," and he keeps this in mind throughout his process.

Working with his dancers, Rincones calls himself "a firm believer in the physicality of the process; it's a physical art." He works to elicit in them a "sensuality of movement" connected to the breath, and to the basic fact of human contact. Using the body as an expressive tool is an inherently sensual act, and Rincones revels in this fact. To enhance his dancers' expressive power, he spends time encouraging them to dig deep into their emotions and sensations, which helps them "to develop as artists, not just as dancers."

What can we expect from this week's concert? From explorations of the poetics of music, breath, and movement will surely emerge passion and excitement -- an excerpt from the endless human story. In Rincones' words, "Movement for me needs to express something human, a reminder of the connections that we have."

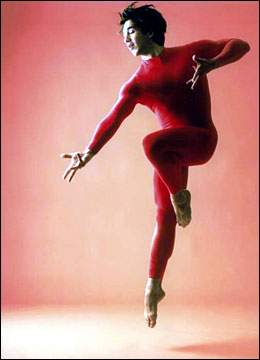

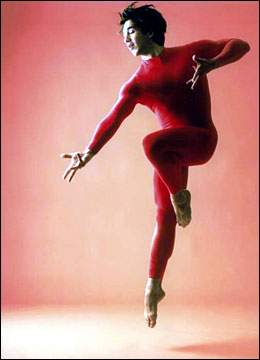

DANCE--On the Move: Breath, water, and the "sensuality of movement"

<a href=www.richmond.com>Richmond.com

Wednesday May 7, 2003

It's a fallacy that "we need to be experts in order to enjoy something," says Juan Carlos Rincones, director of Rincones & Company Dance Theater. He deplores this all-too-common view, and says that the most rewarding thing for him is to connect with an audience, whether or not they are dance connoisseurs. "I feel that every audience member brings their own background, human story, and emotions of the moment" to bear on the interpretation of a performance, Rincones says, and he enjoys hearing comments from people who have seen elements in his work that he may never have intended.

It's a fallacy that "we need to be experts in order to enjoy something," says Juan Carlos Rincones, director of Rincones & Company Dance Theater. He deplores this all-too-common view, and says that the most rewarding thing for him is to connect with an audience, whether or not they are dance connoisseurs. "I feel that every audience member brings their own background, human story, and emotions of the moment" to bear on the interpretation of a performance, Rincones says, and he enjoys hearing comments from people who have seen elements in his work that he may never have intended.

Richmond audiences can draw their own conclusions from Rincones' work Thursday night at the Grace Street Theater, when the director and his company perform here for the first time. The program consists of new work, which Rincones refuses to discuss because he prefers "to have the audience see new pieces without any preconceived ideas," and in the second half, a repertory piece called "Torrentes."

Set to Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Op. 38, "Torrentes" reflects Rincones' "intense commitment to become intimately acquainted with the music." Music is a big component in his choreography, and while that may seem an obvious statement about a dancer, many choreographers work out movement first and find music later, or set work to no music at all. Not Rincones. "Music is my motivator," he says.

"I was very afraid of [the Barber music] at first because I couldn't count it." By approaching the music on his own terms, however, and understanding it as a dancer rather than as a musician, Rincones found he could make his own score through movement, and got past his fear of the concerto's intricacies.

Communicating this approach to his dancers, Rincones encourages them to feel the music through their breathing. Classical ballet, for example, downplays the movement of breath in the body, but Rincones likes to make that movement of breath part of the larger movement of the dance, and so "convey the music in a three-dimensional way." About "Torrentes" he says, "For me, the music evokes the forces of nature; in particular the rushing flow of water I associate with my native Venezuela."

Choreography for Rincones is a "quite uncomfortable" process that involves finding a quiet internal space to work out the progression from music to breath to movement. Once he's moving, he works in "wide brush strokes," sketching out loose movement phrases that he then begins to manipulate and define. Dance, he says, means "trying to communicate with the body," and he keeps this in mind throughout his process.

Working with his dancers, Rincones calls himself "a firm believer in the physicality of the process; it's a physical art." He works to elicit in them a "sensuality of movement" connected to the breath, and to the basic fact of human contact. Using the body as an expressive tool is an inherently sensual act, and Rincones revels in this fact. To enhance his dancers' expressive power, he spends time encouraging them to dig deep into their emotions and sensations, which helps them "to develop as artists, not just as dancers."

What can we expect from this week's concert? From explorations of the poetics of music, breath, and movement will surely emerge passion and excitement -- an excerpt from the endless human story. In Rincones' words, "Movement for me needs to express something human, a reminder of the connections that we have."