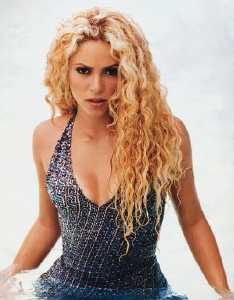

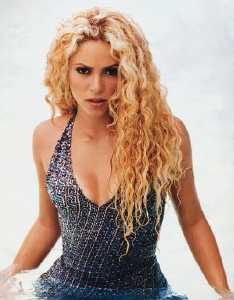

Shakira starts Venezuelan tour in Maracaibo

<a href=>Venezuela's Electronic News

Posted: Friday, May 09, 2003

By: Patrick J. O'Donoghue

Maracaibo has been host to Colombian international pop star, Shakira kick-starting her Venezuelan Mongoose Tour. After the concert in Venezuela's second biggest city, Shakira is due to appear in the Caracas Poliedro (May 9).

Shakira has just concluded a successful tour of Argentina but did run into a few problems with news reporters because of her boyfriend, Antonio de la Rua, said to be very unpopular there ... he happens to be the son of disgraced Argentinean President Fernando de la Rua.

Venezuelan media sources have highlighted the diva's personal life-style ... her current entourage consists of 70 persons and personal security is top of her tour agenda.

The artist will travel in an armored limo complete with fax machine, phones and internet connections.

On a frivolous note, the media is feasting on the revelation that Shakira has asked for a basket of fruit in her dressing room on each concert day.

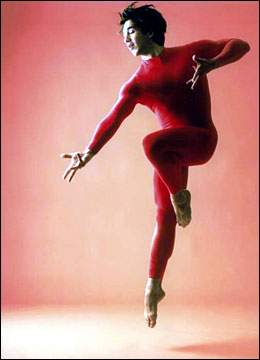

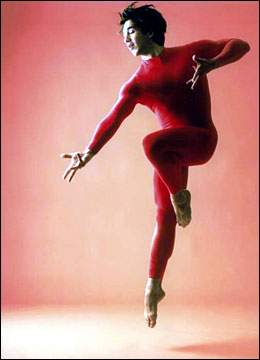

Rincones and Company- Forging His Path

<a href=www.metroweekly.com>

by Jonathan Padget

Published on 05/08/2003

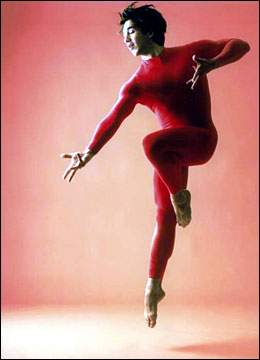

When Juan Carlos Rincones arrived in Washington from Venezuela in 1980 to start his freshman year at The George Washington University, dancing was the furthest thing from his mind.

He'd never set foot in a dance studio in his life, and he was certain he'd be in Washington only as long as it took to earn a degree in civil engineering. So how is it that Rincones has become a 23-year-Washingtonian, the past nine of which have been spent at the helm of one of the city's most esteemed modern dance troupes, Rincones & Company Dance Theater?

It all started with a flier for Joy of Motion Dance Center that Rincones picked up one day in the early '80s while walking in Dupont Circle, despondent over the choice of his first boyfriend, another Venezuelan student, to return home and get married.

"I felt completely abandoned," says Rincones, 40, who was also struggling to come to grips with his sexuality. "I was miserable, I was doing terribly in school, and I couldn't afford a shrink."

Sensing that a dance class just might be the kind of change of pace that would take his mind off his troubles, Rincones signed up for the next one scheduled -- a Friday night course in Afro-Jazz. "It was so therapeutic," he recalls, "because for that hour and a half that the class lasted, you couldn't think about anything else. I experienced such a rush from being able to be out of my turmoil. I got hooked."

Rincones started going to dance classes more often, and engineering classes less, until he eventually decided to focus exclusively on a career as a dancer-choreographer. With his vocational calling in perspective, Rincones also found himself better able to accept his sexuality, and he's built an eighteen-year relationship with noted interior designer Thomas Pheasant.

"Being gay is an undercurrent that's always there in my work," Rincones says. "Dance is, after all, an accumulation of your experiences in order to express something very personal about who you are."

Rincones & Company Dance Theater performs at the Kennedy Center Terrace Theater on Thursday, May 15, at 7:30 p.m. Tickets are $35. Call 202-467-4600. Visit www.rinconesdancetheater.org.

DANCE--On the Move: Breath, water, and the "sensuality of movement"

<a href=www.richmond.com>Richmond.com

Wednesday May 7, 2003

It's a fallacy that "we need to be experts in order to enjoy something," says Juan Carlos Rincones, director of Rincones & Company Dance Theater. He deplores this all-too-common view, and says that the most rewarding thing for him is to connect with an audience, whether or not they are dance connoisseurs. "I feel that every audience member brings their own background, human story, and emotions of the moment" to bear on the interpretation of a performance, Rincones says, and he enjoys hearing comments from people who have seen elements in his work that he may never have intended.

Richmond audiences can draw their own conclusions from Rincones' work Thursday night at the Grace Street Theater, when the director and his company perform here for the first time. The program consists of new work, which Rincones refuses to discuss because he prefers "to have the audience see new pieces without any preconceived ideas," and in the second half, a repertory piece called "Torrentes."

Set to Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Op. 38, "Torrentes" reflects Rincones' "intense commitment to become intimately acquainted with the music." Music is a big component in his choreography, and while that may seem an obvious statement about a dancer, many choreographers work out movement first and find music later, or set work to no music at all. Not Rincones. "Music is my motivator," he says.

"I was very afraid of [the Barber music] at first because I couldn't count it." By approaching the music on his own terms, however, and understanding it as a dancer rather than as a musician, Rincones found he could make his own score through movement, and got past his fear of the concerto's intricacies.

Communicating this approach to his dancers, Rincones encourages them to feel the music through their breathing. Classical ballet, for example, downplays the movement of breath in the body, but Rincones likes to make that movement of breath part of the larger movement of the dance, and so "convey the music in a three-dimensional way." About "Torrentes" he says, "For me, the music evokes the forces of nature; in particular the rushing flow of water I associate with my native Venezuela."

Choreography for Rincones is a "quite uncomfortable" process that involves finding a quiet internal space to work out the progression from music to breath to movement. Once he's moving, he works in "wide brush strokes," sketching out loose movement phrases that he then begins to manipulate and define. Dance, he says, means "trying to communicate with the body," and he keeps this in mind throughout his process.

Working with his dancers, Rincones calls himself "a firm believer in the physicality of the process; it's a physical art." He works to elicit in them a "sensuality of movement" connected to the breath, and to the basic fact of human contact. Using the body as an expressive tool is an inherently sensual act, and Rincones revels in this fact. To enhance his dancers' expressive power, he spends time encouraging them to dig deep into their emotions and sensations, which helps them "to develop as artists, not just as dancers."

What can we expect from this week's concert? From explorations of the poetics of music, breath, and movement will surely emerge passion and excitement -- an excerpt from the endless human story. In Rincones' words, "Movement for me needs to express something human, a reminder of the connections that we have."

DANCE--On the Move: Breath, water, and the "sensuality of movement"

<a href=www.richmond.com>Richmond.com

Wednesday May 7, 2003

It's a fallacy that "we need to be experts in order to enjoy something," says Juan Carlos Rincones, director of Rincones & Company Dance Theater. He deplores this all-too-common view, and says that the most rewarding thing for him is to connect with an audience, whether or not they are dance connoisseurs. "I feel that every audience member brings their own background, human story, and emotions of the moment" to bear on the interpretation of a performance, Rincones says, and he enjoys hearing comments from people who have seen elements in his work that he may never have intended.

It's a fallacy that "we need to be experts in order to enjoy something," says Juan Carlos Rincones, director of Rincones & Company Dance Theater. He deplores this all-too-common view, and says that the most rewarding thing for him is to connect with an audience, whether or not they are dance connoisseurs. "I feel that every audience member brings their own background, human story, and emotions of the moment" to bear on the interpretation of a performance, Rincones says, and he enjoys hearing comments from people who have seen elements in his work that he may never have intended.

Richmond audiences can draw their own conclusions from Rincones' work Thursday night at the Grace Street Theater, when the director and his company perform here for the first time. The program consists of new work, which Rincones refuses to discuss because he prefers "to have the audience see new pieces without any preconceived ideas," and in the second half, a repertory piece called "Torrentes."

Set to Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Op. 38, "Torrentes" reflects Rincones' "intense commitment to become intimately acquainted with the music." Music is a big component in his choreography, and while that may seem an obvious statement about a dancer, many choreographers work out movement first and find music later, or set work to no music at all. Not Rincones. "Music is my motivator," he says.

"I was very afraid of [the Barber music] at first because I couldn't count it." By approaching the music on his own terms, however, and understanding it as a dancer rather than as a musician, Rincones found he could make his own score through movement, and got past his fear of the concerto's intricacies.

Communicating this approach to his dancers, Rincones encourages them to feel the music through their breathing. Classical ballet, for example, downplays the movement of breath in the body, but Rincones likes to make that movement of breath part of the larger movement of the dance, and so "convey the music in a three-dimensional way." About "Torrentes" he says, "For me, the music evokes the forces of nature; in particular the rushing flow of water I associate with my native Venezuela."

Choreography for Rincones is a "quite uncomfortable" process that involves finding a quiet internal space to work out the progression from music to breath to movement. Once he's moving, he works in "wide brush strokes," sketching out loose movement phrases that he then begins to manipulate and define. Dance, he says, means "trying to communicate with the body," and he keeps this in mind throughout his process.

Working with his dancers, Rincones calls himself "a firm believer in the physicality of the process; it's a physical art." He works to elicit in them a "sensuality of movement" connected to the breath, and to the basic fact of human contact. Using the body as an expressive tool is an inherently sensual act, and Rincones revels in this fact. To enhance his dancers' expressive power, he spends time encouraging them to dig deep into their emotions and sensations, which helps them "to develop as artists, not just as dancers."

What can we expect from this week's concert? From explorations of the poetics of music, breath, and movement will surely emerge passion and excitement -- an excerpt from the endless human story. In Rincones' words, "Movement for me needs to express something human, a reminder of the connections that we have."

A video pastiche - a global broadcast services provider

<a href=www.sun-sentinel.com>Sun-Sentinel.comBy Doreen Hemlock

Business Writer

Posted April 20 2003

Visit The Kitchen Inc. in downtown Miami, and you'll find a team of engineers, actors, translators and marketers cooking up cable TV and satellite TV offerings for a global audience.

Upstairs, an engineer takes dubbing from Brazil sent over the Internet and mixes it with film to create a Portuguese-language Dragonball TV episode that can be broadcast back to South America, perhaps by satellite.

Downstairs, employees monitor satellite transmissions of more than a dozen pay TV channels, making sure the cartoons, soap operas, game shows and even Playboy TV programs arrive without a glitch in Mexico, Venezuela, Spain and other countries.

Welcome to the world of broadcast services, the latest stage in South Florida's evolution as a center for international pay TV. The Kitchen exemplifies how much South Florida has matured -- from mainly selling U.S. programs to Latin America into a sophisticated, full-service center that produces, dubs, packages and broadcasts cable and satellite TV programs worldwide.

Today's economic woes in Latin America have helped speed the evolution: In a classic case of turning lemons to lemonade, The Kitchen and its colleagues now are focusing more on Europe, Asia and U.S. ethnic markets, making the industry more global.

"Now, we take the sauce from Brazil, the cheese from Madrid, bake the pizza here in Miami and deliver it anywhere in the world," quipped Venezuela-born Juan Bernardo Alvarez, who heads up The Kitchen's language conversion services.

Only a decade ago, it would have been unthinkable that South Florida could host a broadcast services industry employing more than 1,000 people and featuring Latin American offices of such marquee names as Disney, MTV, HBO, MGM and Discovery.

Back then, Latin American nations were just starting to open their mainly government-controlled telecom markets to private and foreign investment. And satellite links to Latin America were so limited that cable companies couldn't easily send their signals to the region anyway. Industry analysts described the Latin pay TV industry at the start of the 1990s as being at about U.S. levels in the 1970s.

That all changed by the mid-1990s, as many Latin governments welcomed media investment, new satellites were deployed, and new technologies for compressing TV signals allowed all satellites to transmit more efficiently too.

Gary McBride remembers the fever that spread among U.S. companies to enter the new Spanish- and Portuguese-language market overseas. He was among the pioneers, launching Gems TV in Miami in 1993, a channel aimed at Latin women and akin to Lifetime.

"I think we were the fifth pan-regional channel," McBride said. "And within something like 18 months, I counted 70."

South Florida became the hub for the new pay TV industry for the same reasons it had become the gateway to Latin America for other businesses: It had the best airline connections to Latin America, multilingual talent, plus more accessible and affordable telecom and tech offerings than Latin American nations themselves

Arriving late to South Florida, the pay-TV industry also could build on the area's strengths: It could tap into the existing base of Spanish-language TV companies serving the U.S. market, including Hialeah-based network Telemundo. Plus, networks could draw on the hundreds of multinationals with Latin American offices as potential TV advertisers, from banks to hotel companies to software makers.

"You put it all together," McBride said. "It's a slam dunk."

Technology explosion

Since the mid-1990s, South Florida's broadcast services industry evolved for other reasons too: notably, relatively low costs and new technologies.

Greater Miami proved cheaper for TV production than rival sites in New York and Los Angeles, partly because it had little of the union labor that commands higher wages. That cost edge helped sway France Telecom in 1998 to buy Miami-based Hero Productions and invest $18 million in an expansion that now includes one of the biggest TV production studios in the Southeast.

"And in the past two years, those studios have been 100 percent occupied," mostly with shows in Spanish, said Hero founder Roberto "Bob" Behar, now president of France Telecom's Globecast America and dean of the South Florida industry.

New technologies also have spurred business, making it faster and easier to translate and distribute shows worldwide.

Miami Beach-based TM Systems revolutionized translation, dubbing and subtitling with software that earned a coveted Prime Time Emmy Award for Technical Achievement in 2002. The software does away with a decades-old system that had translators working with videotapes, jotting down lines, winding and rewinding tapes, requiring as much as 10 hours to translate a 30-minute show.

The new software instead lets translators work with computers, so they can watch digital versions of TV shows and type translations directly onto the screen, slashing their translation time by nearly a half.

Then, actors can watch the computer screens and get precise, digital cues on when to speak for dubbing a show into Spanish or other languages. And engineers can record the actors' voices directly into the computers, further slashing the time it takes to convert a show like South Park into Spanish or other languages, said Alvarez, The Kitchen's language services chief.

"What took eight hours of recording in one studio, we can now do in as little as an hour-and-a-half using several studios at the same time, if we have an emergency and need to rush out a show," Alvarez said.

High-speed Internet links further spur the business. Now, high-quality audio dubbed in Madrid, Berlin, Bogotá or elsewhere can be sent through computers to Miami for mixing with film and broadcast by satellite. Actors need not gather in a single studio.

South Florida has an edge for those Internet links, too, because it is a hub or "network access point" for many fiber-optic undersea cables that transport audio, video and text files worldwide. Companies in greater Miami have an ample supply of high-speed Internet connections at relatively low costs compared to other major cities, said The Kitchen's general manager, Belgium-born Pierre Jaspar.

"Our business couldn't have existed even six years ago," Jaspar said. "We didn't have the technology or the speed."

Going global

Still, most of South Florida's efforts in international pay TV were geared toward Latin America -- until recently.

Argentina's severe depression and a widespread slump in the Latin region since 2001 have forced companies to focus elsewhere, especially on the fast-growing U.S. Hispanic and multiethnic markets.

Globecast America now uses its Miami facilities to broadcast more than 60 radio and TV channels into U.S. homes on its World TV direct-to-home satellite platform, including some in Arabic, Turkish, German and Romanian. It also sends signals from Miami to Australia, Iran and other distant nations, even though other broadcast service providers may be closer, Behar said.

"When we were bought out by France Telecom, we found it's cheaper to provide service from Miami than from Europe in some cases," Behar said. That's because labor costs in Miami tend to be lower, plus South Florida sometimes has equipment and technical know-how that make its operations more efficient than those in France or elsewhere, he said.

The Kitchen also has expanded beyond its roots as the broadcast service arm of Claxson Interactive Group, a Latin American multimedia conglomerate. Jaspar said about 20 percent of The Kitchen's sales now come from Europe, Asia and Africa, with programs handled in at least 15 languages and an office also recently opened in Spain.

So far, the U.S. and global push from South Florida hasn't fully offset the slump in business to Latin America. The Weather Channel Latin America closed in December after six years of losses, cutting 80 jobs in Miami and Atlanta. And DirecTV Latin America, which operates a Fort Lauderdale office, in March sought protection from creditors under Chapter 11 of the U.S. bankruptcy code. Overall, South Florida's job tally in international broadcast services has slipped from a 2001 peak.

The pay TV industry for Latin America is working to counter the slump partly through a new trade group in Miami, the Latin American Multi-Channel Advertising Council, modeled after the Cable Advertising Bureau in the United States. It aims to boost the share of ad revenue spent on cable and satellite TV channels in the Latin region far beyond the $250 million spent in 2001.

But executives say South Florida's industry is sure to rebound, as the global economy picks up.

At The Kitchen, they're ready to mix up more batches of South Park and Brazil's El Clon to distribute worldwide.

Doreen Hemlock can be reached at dhemlock@sun-sentinel.com or 305-810-5009.