The dangers of democracy

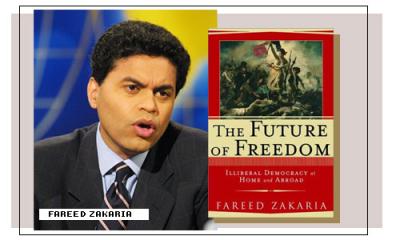

This season's intellectual pinup, Fareed Zakaria, author of "The Future of Freedom," explains why the romantic myth of freedom could harm Iraq -- and why power elites aren't so bad.

By Michelle Goldberg

April 21, 2003 | Since Sept. 11, hawks in the Bush administration have presented themselves as evangelists for democracy. The absence of democracy, in the neoconservative analysis, creates the climate of desperation and frustration that breeds extremism. Democracy's introduction into the Middle East, via regime change in Iraq, would bring a bracing new spirit of liberty to the region, undermining the stagnant authoritarianism of Iraq's neighbors.

Yet were it implanted tomorrow, democracy in most of the Middle East would bring to power the very totalitarian theocrats who most menace us. Indeed, argues Fareed Zakaria in his incisive new book "The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad," democracy isn't necessarily the opposite of tyranny. From Venezuela to Kazakhstan, the last decade has seen a rise in elected autocrats, challenging American bromides that posit universal suffrage as the answer for all the world's ills.

The book and its 39-year-old author, the editor of Newsweek International, is getting an extraordinary amount of attention. In New York magazine, Marion Maneker gives him the movie star treatment, writing, "Dimple-chinned, with expressive eyebrows and a thick head of black hair, Fareed Zakaria could easily be the Indian reincarnation of Cary Grant." He may be the first of a new, post Sept. 11 breed -- the policy wonk as sex symbol.

For all the buzz he's generating, Zakaria's ideas about democracy's failures aren't that new -- in much of the foreign-policy establishment, they've become a kind of conventional wisdom, popularized by writers like Robert Kaplan and Amy Chua. It's clear to anyone who's been paying attention, after all, that the heartening triumph of democracy around the world in the last decade has coincided with brutal outbreaks of ethnic nationalism, civil war and genocide.

Yet Zakaria's book goes further than others, scanning the history of Western culture and identifying a series of fallacious assumptions about the roots of liberty that threaten not just fledgling Third World republics, but America as well: "Western democracy remains the model for the rest of the world, but is it possible that like a supernova, at the moment of its blinding glory in distant universes, Western democracy is hollowing out at the core?"

Freedom, Zakaria argues, comes not from politicians' slavish obeisance to the whims of The People, divined hourly by pollsters. It comes from an intricate architecture of liberty that includes an independent judiciary, constitutional guarantees of minority rights, a free press, autonomous universities and strong civic institutions.

In America, all of these institutions have been under consistent attack for the last 40 years from populists of the left and right seeking to strip power from loathed elites and return it to the masses. "The deregulation of democracy has ... gone too far," Zakaria writes.

Much of what Zakaria writes will anger liberals. He criticizes 1970s reforms that opened up the closed workings of Congress to the public, arguing, "The purpose of these changes was to make Congress more open and responsive. And so it has become -- to money, lobbyists, and special interests." The World Trade Organization is opposed by anti-globalization activists in part because of its secretive, unresponsive nature, but Zakaria argues that's precisely why it works.